James Russell, RN-BC, MBA, CVAHP, Value Analysis Program Director, UW Health, WI

I have been thinking a lot lately about not only what value analysis is (definition) and how value analysis is done (process), but where value analysis is going (future state). Ours is a strange profession in that there aren’t decades upon decades of lessons learned to draw upon. Being relatively young, at least in the healthcare field, provides us with great opportunities, but also allows an incredible amount of variation in what we all think value analysis really is (our scope). The running joke among GPO consultants is, “If you’ve seen one VA program, you’ve seen one VA program.” There’s certainly truth in that. A strength in our scarcity is that we rely on an immense amount of networking with each other. There are more than 15,000 employees in my health system. I could fit all of the value analysis folks in one car! This “lack of peers” forces us to collaborate with other health systems and that’s a very good thing.

When I encounter people interested in what I do, I often refer them to a couple of sources, one of which you’re reading now. How wonderful is it that an internet search for “healthcare value analysis” turns up, on its first page, a reference to this very magazine? Where else can you find not only the latest issues and topics important to our field, but back issues with great articles…for free? Another source is our professional association, Association of Value Analysis Professionals (AHVAP). This is also a treasure trove of information for those who are not quite sure what VA means. I’ve often told an audience, “You all know what the words value and analysis mean…that does not mean you understand what the profession of value analysis is. That’s like thinking you understand what an industrial engineer does because you’ve seen a factory (industry) and ridden on a train (driven by an engineer). ”

I spent the first few years of this career learning about health system supply chain logistics, procurement, materials management, and GPOs. After a few years, I “graduated” to the all-important understanding of the power of utilization. I say “graduated” as homage to one of my early mentors, Todd Bowers from LA County/USC. I was bragging to an audience about a utilization project that exceeded expectations and he said, “Great…you’ve passed value analysis 101!” It irked me. Can you tell I’m a sensitive little snowflake? Okay, that might be a stretch, but you get the point. He was absolutely right. I was beginning to see the value beyond the price tag. Some things, only experience can teach. Try to explain the utilization of products, equipment, and technologies to someone outside of healthcare and their eyes glaze over. Which one of you has the perfect answer to the, “What do you do for a living?” question at a party? Share it with me…please! My answer takes 5 minutes to say and still confuses people.

I spent the first few years of this career learning about health system supply chain logistics, procurement, materials management, and GPOs. After a few years, I “graduated” to the all-important understanding of the power of utilization. I say “graduated” as homage to one of my early mentors, Todd Bowers from LA County/USC. I was bragging to an audience about a utilization project that exceeded expectations and he said, “Great…you’ve passed value analysis 101!” It irked me. Can you tell I’m a sensitive little snowflake? Okay, that might be a stretch, but you get the point. He was absolutely right. I was beginning to see the value beyond the price tag. Some things, only experience can teach. Try to explain the utilization of products, equipment, and technologies to someone outside of healthcare and their eyes glaze over. Which one of you has the perfect answer to the, “What do you do for a living?” question at a party? Share it with me…please! My answer takes 5 minutes to say and still confuses people.

So here we are, at my 10th year in healthcare value analysis; my 30th year as a Registered Nurse. Where do I want to see value analysis go? How can we maximize our expertise and translate what we do to people who don’t have time to get into the weeds? Of course, I have some thoughts about this.

Definition

First, when defining what VA is, the AHVAP website has a great one that I won’t quote, but here’s a link to it http://www.ahvap.org/?page=about_ahvap. It’s been updated in the last few years and serves as an excellent source for folks who’ve never heard of this line of work. I use it (and cite it, of course) in presentations all the time. I, however, have also made my own version. This is not to compete with AHVAP (who am I, after all?) but to personalize the definition and perhaps speak to a different audience…healthcare professionals (who I’m usually asking to change their practice). Here’s what I tell them:

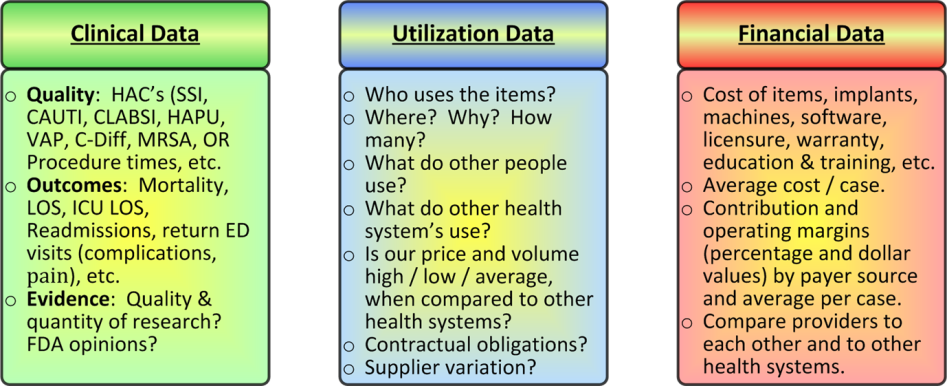

Healthcare Value Analysis (HVA) is the practice of creating a measureable and sustainable impact upon a health system’s fiscal and quality outcomes. This is accomplished by using data-based decision making techniques to influence unwanted variation. This undesirable variation is identified by suboptimal financial performance, unfavorable clinical outcomes, or both. This variation is recognized by thorough:

Healthcare Value Analysis (HVA) is the practice of creating a measureable and sustainable impact upon a health system’s fiscal and quality outcomes. This is accomplished by using data-based decision making techniques to influence unwanted variation. This undesirable variation is identified by suboptimal financial performance, unfavorable clinical outcomes, or both. This variation is recognized by thorough:

- Examination of evidenced-based clinical data

- Analysis of product, equipment, and technology utilization data

- Scrutiny of objective financial data

A robust value analysis process combines specifics from all three entities to deliver a total package of value. This results in deliverables that encourage objective decision making that is transparent and actionable, and return on investment (ROI) calculating that is impartial and reproducible.

Okay, so it’s a mouthful! One of the things I’m trying to get across is that we’re not all about new products! Sure, we have involvement in them, but that’s not why you pay us to do what we do. You also may notice that I’ve modified the tried and true “Cost, Quality, and Outcomes” (CQO) movement from the Association for Healthcare Resource & Materials Management (AHRMM)[1]. This is because I believe Quality and Outcomes can be combined, and I do so in the “clinical data” bucket. Again, this is not to quibble with the experts, just to put my own spin on it.

Process

Hidden within my definition above is a nod toward the process. I talk about using data-based decision making techniques. Which of us would argue with that? Don’t we all preach about evidence-based practice? Well, in value analysis, data is our evidence. Where I go a little out on a limb is the next phrase: “…to influence unwanted variation.” This is where I want to spend my time, and the rest of my career. It’s the fun stuff.

Value analysis professionals sit in a unique position to be able to understand the three facets of my pie chart: clinical, financial, and utilization data. Clinicians understand their world, finance professionals get theirs, but very few understand the power of utilization. That’s where value analysis folks shine. The variation in who uses what, where they use it, why they use it, how they use it, how many they use, how they compare to what other people use, how they compare to what other health systems use, which suppliers are involved, etc., is why I get excited when telling people what I do for a living. Really, I do!

I have a great example of one of my health systems having the best price in the nation on a particular item…so Procurement has done a great job on the vendor contract. However, we also had the highest utilization of any hospital in the nation…we ought to have the lowest price! Diving deeper, we found that there were health systems many times bigger than ours that used fewer “eaches” of this item annually. What made us so special? Were our patients unique? Not so much. It turns out that through the best of intentions we had protocols in place that encouraged inappropriate use of the widget. By changing our practice (there’s that word again), we were able to shave a cool million dollars off of our annual supply costs without having a negative impact on what the item was used for! This is why I show utilization as the submerged portion of the iceberg in presentations. It takes a combination of clinical and business knowledge to ferret it out.

I have a great example of one of my health systems having the best price in the nation on a particular item…so Procurement has done a great job on the vendor contract. However, we also had the highest utilization of any hospital in the nation…we ought to have the lowest price! Diving deeper, we found that there were health systems many times bigger than ours that used fewer “eaches” of this item annually. What made us so special? Were our patients unique? Not so much. It turns out that through the best of intentions we had protocols in place that encouraged inappropriate use of the widget. By changing our practice (there’s that word again), we were able to shave a cool million dollars off of our annual supply costs without having a negative impact on what the item was used for! This is why I show utilization as the submerged portion of the iceberg in presentations. It takes a combination of clinical and business knowledge to ferret it out.

More about my process: It takes several dynamics into account…not just looking at costs. As in the example above, if we started to experience negative clinical outcomes, due to our change in practice, that would necessitate a quick re-evaluation of what we were doing. Things can’t happen in isolation. We can’t save money at the expense of clinical outcomes. We also can’t save the world clinically and not look at our expenses. Hospitals go bankrupt that way. The dance between these variables occurs in the realm of utilization. Again, that’s the fun stuff.

Of late, I have been adding more and more variables to this process, “…to deliver a total package of value,” that I find fascinating. I hope you do, too. I recently began looking at supply cost variation, by surgeon, for a specific operating room procedure. As per usual, I am looking for variation in the data, and then asking, “What are we getting for this variation?” The data fell into different categories:

- Supply Cost per case: Some surgeons used higher-cost items (staplers) and others did not (sutures).

- OR Procedure time: Some surgeons took much longer to perform their procedure than their peers. (This can be a bit skewed by our being a teaching hospital and whether or not there are residents in the room…it takes time to teach!).

- Length of Stay: Some surgeons had longer average inpatient lengths of stay (LOS) than their colleagues.

- Infection rates: Do faster surgeons have fewer complications? In this case, not so much.

- Readmission rates: Do patients who stay longer in the hospital (longer LOS), get readmitted less often? In this case, not so much. This one gets the finance people excited, due to Value Based Purchasing and lack of reimbursement!

There are more (like reimbursement, etc.), but this is a good starting point. Upon examining the clinical, financial, and utilization data, we found some variation. One of our surgeons spent a lot more money on high-cost items (like staplers and reloads) than her colleagues. When asking our question, “What are we getting for this variation?” the answer was…nothing. Her LOS wasn’t shorter. Her OR Procedure time wasn’t shorter. Her infections, readmissions, and/or return visits to the ED for pain control weren’t less than her colleagues’. She just spent more money. Upon showing her the data, she went, “Oh…I had no idea. I can use fewer staplers and tie knots…I’m good at it. I didn’t realize there was such a difference in cost.”

This interaction reinforced my common reference to the 80/20 rule. If we show practitioners accurate, concise, and meaningful data, 80% will look at extreme variation and change their practice without being asked to. Who wants to be the most costly practitioner with nothing to show for it (no better outcomes)? The other 20% take a little more time to influence. I could go on and on (as many of you know), but I’ll stop here.

Future State

Where do I want to see value analysis go? Keep in mind, this is my opinion…by no means is it meant to convey a consensus, a majority, or even hint that anyone other than myself feels this way. I have seen some of my colleagues change their phrasing to value management instead of analysis (another mentor, Barbara Strain at the University of Virginia). I like that. I like the concept of changing the title. I’m not sure it’s where we’ll end up; “analysis” is what I love to do, being a data geek, and “leadership” is usually a better word than “management,” but I like that we’re looking at different terms. I am often critical (nicely) of my customers who rely on TTWWADI as a rationale for being resistant to change. “That’s the way we’ve always done it” is only a good explanation for behavior if that behavior is perfect! Otherwise, it’s just an excuse. We value analysis professionals have to be careful not to fall into that trap ourselves. Looking at our profession with new eyes can only help us improve. Isn’t that what we’re all about anyway?

I’d love to see our profession morph into a position of strength and influence in the health systems we work in. This is not to disparage where we are now, but we could do so much more! I have seen companies with senior leaders called, “Chief Client Officer”, or “Chief Empowerment Officer”, or “Senior Vice-President of Patient Experience”, etc. I’m sure those are interesting and potentially effective roles, but how about “Chief Value Officer”? How much of a return on investment could such a leader show? I think it could be substantial. It’s not, of course, just about a title. It’s about influence. If health system departments had to explain their variation in terms of, “What are we getting for this?” to someone who understood both the business (financial) and clinical worlds, I’m betting significant unnecessary expenses could be avoided and “tons” of waste identified (see what I did there?).

I’d love to see our profession morph into a position of strength and influence in the health systems we work in. This is not to disparage where we are now, but we could do so much more! I have seen companies with senior leaders called, “Chief Client Officer”, or “Chief Empowerment Officer”, or “Senior Vice-President of Patient Experience”, etc. I’m sure those are interesting and potentially effective roles, but how about “Chief Value Officer”? How much of a return on investment could such a leader show? I think it could be substantial. It’s not, of course, just about a title. It’s about influence. If health system departments had to explain their variation in terms of, “What are we getting for this?” to someone who understood both the business (financial) and clinical worlds, I’m betting significant unnecessary expenses could be avoided and “tons” of waste identified (see what I did there?).

Variation isn’t always negative. Sometimes the explanation is just fine, even if it isn’t logical. If the reason your hospital has 20 different suppliers for spinal implants is that you only have three surgeons and two will leave and go to your competition if you try to narrow the field, pick a different battle to fight! It may not pass the rationality test, but it passes the reality test. Determining if the explanation for variation is credible can’t be left up to the department in question. You can’t leave it up to the orthopedic department to influence the variation in demand by matching implants by themselves. That’s not their core competency. Their job is to do surgery. Hopefully, lots of it! These decisions (giving credibility, or not, to variation explanations) are better made at the senior leadership level with an objective eye.

Last example: Senior leadership is also culpable in making poor decisions. I know of an academic medical center that replaced perfectly good imaging equipment (MRIs, CT scanners) because the newly recruited Chief of Radiology preferred a different manufacturer. That new Chief was gone in two years and they had to recruit another one. Guess what company the new guy wanted? You guessed it, the old company. We have to stop doing things like this. I think a Chief Value Officer could help.

Back to my definition: “…resulting in deliverables that encourage objective decision making that is transparent and actionable, and return on investment (ROI) calculating that is impartial and reproducible.” Another mouthful! This is what I hope the future of value analysis becomes; when we treat our decisions like a researcher treats their clinical trial…we must have objective evidence that provides the same end-results, regardless of who’s running the data. Perhaps then, value analysis (or management) will become an absolute necessity in every health system in the country, and not just a “nice to have.”

James Russell, RN-BC, MBA, CVAHP, is the Value Analysis Program Director at UW Health (the University of Wisconsin). Jim has 3 decades of nursing experience; a third in critical care, another third in psychiatry, and the last 10 years in healthcare value analysis. He’s been in both staff and leadership positions in the for-profit, community healthcare sector, as well as in several Academic Medical Centers. Jim has published dozens of articles on value analysis and nursing leadership, and speaks regularly at national conferences. You can contact Russell with your questions or comments at jrussell@uwhealth.org