Cheryl Campos, DNP, RN-BC, CEN, CPHQ, Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital

Francie Moehring, PhD, Boston Strategic Partners

Halit O. Yapici, MD, MBA, MPH, Boston Strategic Partners

Peripheral Intravenous Lines in Patients with Difficult Venous Access

Nearly 90% of the patients who are admitted to hospitals receive a vascular access device.1 The vast majority (95%) of them are peripheral intravenous (PIV) lines,2 which are simple, inexpensive catheters.3 PIVs are typically used to deliver non-irritating fluids, medications, and blood products as well as for blood draws after being inserted into the peripheral veins (i.e., vessels of the hand, forearm, or region of the antecubital fossa).4 Despite their prevalent use, there are several challenges associated with PIV catheters including low rates of successful first-time insertion attempts (~47%) and short dwell times (~1.5 days), which may lead to frequent IV restarts.5 Ultimately, repeated attempts and frequent replacements may increase the risk of catheter-related complications and reduce patient satisfaction.5,6

PIV insertion presents additional challenges for patients with difficult venous access (DVA).6-8 Patients may present with DVA due to a variety of characteristics including age, vein size, pre-existing conditions (i.e., obesity, diabetes, chronic kidney disease) or other medical factors (i.e., chemotherapy patients or patients who previously abused intravenous drugs).5,7-10 Furthermore, the number of these patients is likely to increase due to an aging population as well as the rising prevalence of chronic conditions such as obesity and diabetes.11-14 When using conventional PIVs, DVA patients may require multiple cannulation attempts delaying treatment and increasing the risk of catheter-related complications, which are associated with increased costs and length of stay.5,6,9 Additionally, repeated placement attempts and frequent catheter replacements may lead to a progressive depletion of peripheral veins.15 As a result of the exhaustion of peripheral vasculature, patients may be escalated to more invasive and higher cost forms of vascular access such as central catheters.6,16-18

Utilizing Advanced Peripheral Vascular Access Technologies

Advances in peripheral vascular access technologies may provide more appropriate options compared to conventional PIV catheters. For example, AccuCath® (Becton Dickinson [BD], Franklin Lakes, USA) is a guidewire assisted peripheral intravenous catheter (GAPIV), which supports ultrasound visualization thanks to its echogenic needle. This novel GAPIV includes an integrated guidewire allowing the clinician to guide the needle and confirm successful placement.5 The unique coiled tip of the guidewire prevents vessel damage and posterior vessel wall perforation by entering the vein prior to catheter advancement.5

A randomized clinical trial comparing AccuCath® to conventional PIV catheters demonstrated several clinical advantages including (I) reduced overall complication rates from 52% to 8% (i.e., infiltration, leaking, infection, phlebitis, occlusion, dislodgement, and patient-reported pain); (II) improved first-time insertion rate (89% vs. 47%, respectively); (III) extended dwell times (4.4 days compared to 1.5 days for conventional PIVs); and (IV) increased patient satisfaction.5 The improvement in first-time insertion success rates is likely due to decreased vessel damage, which may lead to longer dwell times and reduce the need for multiple IV restarts.5

The utilization of advanced technologies may also provide economic benefits, which are illustrated by the same clinical study. Despite having a higher per-unit price, AccuCath® led to lower overall costs by requiring approximately 50% fewer PIV components thanks to longer dwell times and higher success rates for the initial insertion attempt.5 Furthermore, AccuCath® may achieve additional cost savings by decreasing the need for more expensive central lines.16,17

Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital

Founded in 1953, Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital is the cornerstone of Salinas Valley Memorial Healthcare System, which serves communities throughout the Salinas Valley, Monterey Peninsula, and the surrounding region of California.19

The 263-bed acute care hospital employs more than 300 board-certified physicians across a broad spectrum of specialties19 and houses an emergency department (ED) providing care for roughly 44,000 patients annually.7

One of the main goals of Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital is to utilize the latest medical techniques with state-of-the-art technology to improve the health and well-being of their patients.19 Therefore, the hospital had already staffed nine diagnostic imaging (DI) nurses who were trained in using ultrasound for placing peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) as well as midlines.7 These nurses are considered experts in vascular access device placement and were typically called to assist when an inpatient nurse was unable to attain venous access.

A Path to Improve Care for DVA Patients

A Path to Improve Care for DVA Patients

A nurse with 20 years of Emergency Department experience, Dr. Cheryl L. Campos, always believed that patients should receive the most appropriate care and receive it with comfort. Therefore, she showed great interest when she learned about AccuCath®, which is a promising option to improve the quality of care.7 Being aware of the historical challenges that DVA patients face regarding catheter insertion, she immediately recognized the opportunity and pitched her idea to improve patient experience at Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital to her colleagues.

Considering that roughly 17% of their patients faced difficulties regarding catheter insertion,7 Cheryl received support from other clinicians who agreed with the potential value, and were motivated to evaluate the current situation and identify challenges and create solutions.7 The team identified three areas for improvement. First, even though the hospital had a specialty nurse team consisting of DI nurses, their use of ultrasound visualization was mostly limited to PICCs and midline placement. Second, there were no clear guidelines regarding when to call specialty nurses for assistance. The lack of a clear workflow led to variations/inconsistencies in practice (i.e., certain inpatient nurses immediately called for assistance after a single failed insertion attempt while others escalated the case only after numerous needle attempts).7 Third, there was a limited number of DI nurses who were primarily available during daytime on weekdays with limited availability on the weekends, which made it harder to utilize these resources after-hours.7 A larger vascular access specialty nurse team with increased availability was needed to avoid delays in patient care and patient discomfort due to multiple placement attempts.7

Considering the opportunities and challenges that were identified, the team drafted an initiative to improve vascular access practices, particularly for DVA patients. The initiative included: (I) receiving authorization from Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital to adopt the novel GAPIV, AccuCath®; (II) establishing a step-by-step workflow to identify and treat DVA patients; and (III) increasing the number and availability of advanced-skilled nurses who are trained to perform GAPIV insertion using ultrasound guidance. Overall, the team wanted to create an efficient and evidence-based workflow to provide the most appropriate care for all patients while prioritizing patient comfort, regardless of the time of day or the day of the week.

Achieving the Stakeholder Buy-In

The first task of the team was to obtain permission for the use of AccuCath® at Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital. For this, it was essential for the team to receive support from multiple committees (i.e., value analysis committee) consisting of both clinical and non-clinical stakeholders, which required presenting the potential clinical benefits as well as economic evidence. Therefore, the team recruited allies such as a nurse manager and a physician in the ED, who advocated the clinical benefits of adopting a GAPIV along with a clear workflow to identify/treat DVA patients. Approval to go forward with product use and training was achieved in July 2016.

The team also performed an in-depth cost analysis based on an economic model supplied by the vendor, which was especially useful in convincing hospital leadership.7 After numerous meetings with a wide range of stakeholders, the team was able to receive support to use AccuCath® and finalize/implement the initiative in four units of Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital: (I) general medical/surgical unit; (II) orthopedic, neurological and spine unit; (III) renal medical/surgical unit; and (IV) oncology unit.

From the Literature to Practice

Identifying the Standards

After receiving widespread support from the stakeholders, the project team proceeded to establish the standards which would feed into an evidence-based three-step workflow to identify and care for DVA patients. The team conducted a literature review using ProQuest Central, Ovid, CINAHL, and PubMed Central to research recent (2012-2017) developments and standards in vascular access. Overall, the search yielded 11,700 articles, 29 of which were found directly relevant after screening.18

The findings from the literature provided recurring themes based on Infusion Nurses Society Standards of Practice, including limiting the number of PIV attempts (no more than 2 attempts/nurse or 4 attempts in total) and utilizing vascular visualization technology for the patients with DVA.18,20 When implemented, these recommendations20 could lead to improved outcomes since limiting the number of placement attempts has been demonstrated to increase patient satisfaction and increase clinical efficiency.6,20,21

Creating an Evidence-Based Workflow

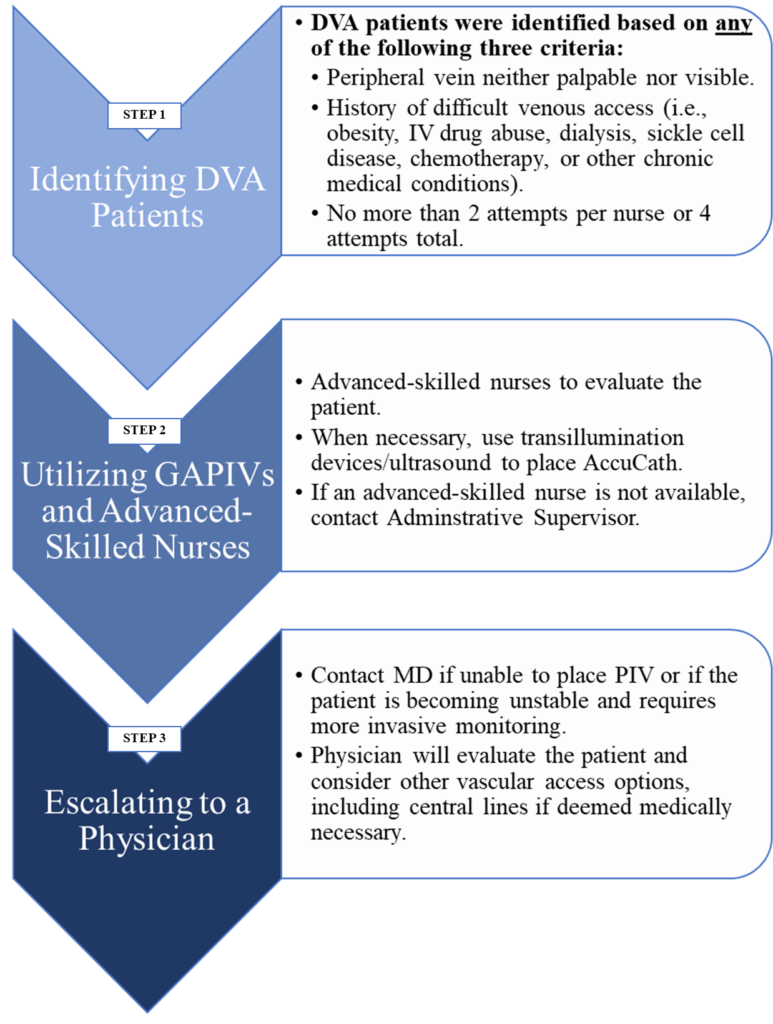

After establishing the standards, the team created a three-step workflow for inpatient nurses to identify the DVA patients and to utilize advanced technologies/advanced-skilled nurses effectively (see Figure: “Workflow to Identify/Treat DVA Patients”).18 The workflow was especially helpful in streamlining the process for identifying patients who could benefit from AccuCath®. Furthermore, it prioritized the selection of the least invasive intravenous access device that supports the patient’s needs and avoided the over-utilization of more invasive catheters when not medically necessary, which was recommended by literature.6,22

Step 1- Identifying DVA Patients:

The first step in the workflow included visually inspecting and/or palpating peripheral veins, followed by an assessment of the medical and vascular access history for certain chronic illnesses (i.e., diabetes, hypertension, or sickle cell disease) that can affect peripheral vasculature.5,7-10,18 When a patient was classified as DVA based on either one of these assessments, the inpatient nurse was to proceed to the second step. The inpatient nurses also advanced to Step 2 when a patient was determined to be DVA based on the number of PIV insertion attempts (no more than 2 attempts/nurse or 4 attempts in total).18

Step 2- Utilizing GAPIVs and Advanced-Skilled Nurses:

The case was elevated to the second step when a patient was identified as DVA in Step 1. Step 2 instructed the inpatient nurses to call an advanced-skilled nurse for assistance, who received specific training in ultrasound-guided AccuCath® insertion. The advanced-skilled nurse would then evaluate the case and, when necessary, place AccuCath® using ultrasound guidance. When an advanced-skilled nurse was not reachable (such as after-hours), the workflow instructed inpatient nurses to contact their administrative supervisors to determine whether any other advanced-skilled nurses were available to provide assistance.18

Step 3 – Escalating to a Physician:

When the advanced-skilled nurse was unable to place a PIV, or the patient became unstable, the case was escalated to a physician who would consider other vascular access options including central venous catheters.18

Workflow to Identify/Treat DVA Patients

Building Capacity

The standardized three-step workflow was expected to increase the demand for the advanced-skilled nurses with special training in GAPIV placement, which could not be met solely by the DI nurses. Therefore, Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital built capacity by providing specialized trainings for the DI nurses as well as additional advanced-skilled nurses in ultrasound-guided insertion of AccuCath®. The product education and training programs were provided by the vendor, which consisted of an online ultrasound course, 4-hour didactic course with practice using ultrasound and inserting the AccuCath® on a gel block, followed by at least two educator supervised training sessions. To complete the training, nurses had to receive a minimum of two 4-hour supervised shifts during which three successful AccuCath® placements had to be completed.7

Initially, three DI nurses and three Emergency Department nurses interested in vascular access were enrolled in the training. This pilot group helped the team to identify characteristics of nurses (i.e., passion and skill for vascular access) who would make the best candidates to serve as advanced-skilled nurses. By August 2017, a total of 40 nurses received specialized training in GAPIV insertion, 34 of which completed all portions of the program. These 34 nurses were then certified as advanced-skilled nurses who could assist other nurses when a case was escalated to the second step of the workflow.7

Implementing the Initiative

It was essential for each stakeholder to fully understand their role in the three-step workflow for successful implementation. Therefore, the team employed a range of communication strategies to ensure a smooth transition for three major stakeholders: medical/surgical inpatient nurses, administrative supervisors, and DI/advanced-skilled nurses. First, the inpatient nurses were introduced to the three-step workflow with a demonstration of a step-by-step example. Eleven inpatient nurses who displayed an interest in taking more responsibility were then selected to become unit project champions. Their role was to encourage their colleagues to follow the guidelines and act as a resource to answer any questions that arose.7 Second, the team presented the three-step workflow at the DI staff meeting where they emphasized the importance of accurately documenting the number of PIV attempts for evaluation purposes. Finally, nursing administrative supervisors and DI nurses were notified regarding a potential increase in the requests for assistance in PIV placement.

To initiate the project, a complete list of the advanced-skilled nurses was created, including the unit he/she worked on and shift information. The initiative was simultaneously rolled out in four units of the hospital: a general medical/surgical unit, a renal medical/surgical unit, an orthopedic, neurological and spine unit, and an oncology unit.

Clinical and Economic Outcomes: Initial Observations

Following the implementation of the three-step workflow and adoption of GAPIV technology, clinicians observed several clinical and efficiency benefits. Nurses reported a decrease in the total number of PIV attempts, especially in DVA patients,7 since the first step of the protocol was to identify DVA patients early on, limit the number of catheter insertion attempts, and escalate the case to an advanced-skilled nurse. Furthermore, the clinical staff noted longer dwell times for GAPIV catheters compared to traditional PIVs,7 which was expected based on the literature.5 The number of central line placements were also reduced due to utilization of GAPIV technology and advanced-skilled nurses.7 The decreased use of central catheters was expected, since the vascular visualization technology increases the success rates of peripheral cannulation, which may eliminate the need for a central device, when other indications are not present for a more invasive vascular access.20 Overall, these improvements were welcomed by most patients. In fact, several nurses experienced patients specifically asking for GAPIV insertion after experiencing the advantages of utilizing newer technologies as well as a specialized workforce.7,18

Provider satisfaction and efficiency have also likely improved due to the initiative.7 Nurses reported that having a clear protocol and the larger number of advanced-skilled nurses increased their productivity and decreased the wait-times.7 Moreover, the cases were less likely to be escalated to the MDs for central line placements, which freed up time for physicians to be spent on other patient care activities.7 These observations suggest a significant improvement in clinician satisfaction as well as a lower utilization of IV resources including central catheters.7,18

Quantifying the Outcomes and Limitations

The team used a conservative evaluation method to quantify the potential benefits of the initiative, where nurses reported outcome measures such as dwell times, the number of insertion attempts, and the number of calls for assistance. Strict exclusion/inclusion criteria were applied, and the reports were only included in the analysis if all data points (i.e., catheter removal date, number of insertion attempts) were complete. Furthermore, the reported values had to match across multiple platforms (i.e., electronic medical records, paper audits for DVA), which resulted in a low sample size (N=24) since a large number of patients had to be excluded due to missing or non-matching values.18

Although this study had a low sample size and the effects did not achieve statistical significance, the evaluation provided important clinical insights. Hospital-wide data from the four-week project timeframe indicated that a total of 59 patients received the GAPIV out of 148 requests for assistance.18 The average number of attempts required to place an AccuCath® device was less than conventional PIV catheters (1.50 versus 1.71, p=0.57) but did not achieve statistical significance. Additionally, AccuCath® consistently demonstrated longer dwell times, averaging nearly double the dwell times compared the standard PIV catheter.18 However, further studies with a larger sample size are needed to confirm these results.

Although this study had a low sample size and the effects did not achieve statistical significance, the evaluation provided important clinical insights. Hospital-wide data from the four-week project timeframe indicated that a total of 59 patients received the GAPIV out of 148 requests for assistance.18 The average number of attempts required to place an AccuCath® device was less than conventional PIV catheters (1.50 versus 1.71, p=0.57) but did not achieve statistical significance. Additionally, AccuCath® consistently demonstrated longer dwell times, averaging nearly double the dwell times compared the standard PIV catheter.18 However, further studies with a larger sample size are needed to confirm these results.

The nurse-reported evaluation method introduced an important limitation regarding underreported failed insertion attempts, which may happen in multiple ways. First, nurses are likely to underreport the PIV insertion failures by other nurses who attempted insertion on the same patient before calling for assistance.7 Second, the inpatient nurses may underreport their total number insertion attempts in order to demonstrate better performance.7 Therefore, the true impact of utilizing GAPIVs is challenging to capture in a nurse-reported evaluation and other methods should be considered in future research. These limitations should be addressed in future research to determine the true clinical and economic outcomes.

Adhering to the Protocol and Sustaining the Improvements

The continued use of the three-step workflow, as well as the effective utilization of new technologies and advanced-skilled workforce, was crucial for the sustainability of the initiative. Therefore, the hospital monitored medical units and addressed any issues that arose. For example, the team identified an issue where a nightshift administrative nursing supervisor misinterpreted the first step of the protocol and directed the nursing staff to escalate cases to Step 2 only after four failed insertion attempts. However, the workflow required immediate escalation to the second step when a patient was identified as DVA after visual inspection and/or the assessment of medical history. The situation was quickly resolved by the team, who stepped in, reinforced the correct workflow, and provided additional training to the staff.

Several inpatient nurses in the medical/surgical units were surveyed post-implementation to determine the long-term impact of the initiative. Responses showed that even several months after the initiative was complete, the units continued to utilize the three-step workflow to identify and treat DVA patients.7 Nearly four years later (as of April 2020) the hospital trained 32 additional nurses and now has 66 nurses trained to insert AccuCath with ultrasound guidance throughout the hospital, demonstrating Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital’s continued commitment to its patients. Furthermore, at the end of 2017, the IV Therapy Policy at the hospital was updated to include the recommendations from the workflow including (I) using vein visualization equipment when placing PIVs when necessary; and (II) limiting the number of insertion attempts to no more than two per nurse or four attempts in total.7,18

Final Thoughts

This case study demonstrates that a handful of motivated clinicians can make a difference for the patients. Clinical practice was improved by developing an evidence-based three-step workflow to identify patients who would benefit from the GAPIV technology and a specially trained workforce. Overall, Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital recognized the importance of providing the most appropriate care to DVA patients while ensuring that they can receive this care with comfort. The needs of the patient subgroups may differ based on a variety of medical factors; therefore, hospitals should utilize evidence-based technologies and methods to provide the best care for all patient populations.

Halit Onur Yapici,

Senior Consultant

Boston Strategic Partners, Inc.

4 Wellington Street Suite 3 Boston, MA 02118

Disclosure: The development of this anecdotal hospital experience was sponsored by BD. Dr. Campos is an employee of Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital and is contracted as a speaker for BD. Dr. Moehring and Dr. Yapici are employees of Boston Strategic Partners Inc., contracted by BD to conduct the primary research and write the study.

References

- Helm RE, Klausner JD, Klemperer JD, Flint LM, Huang E. Accepted but Unacceptable: Peripheral IV Catheter Failure. Journal of Infusion Nursing. 2015;38:189-203.

- Inc iR. European Market Report for Peripheral Intravenous Catheters2016, iData Research Intelligence Behind the Data.

- Cheung E, Baerlocher MO, Asch M, Myers A. Venous access: A practical review for 2009. Paper presented at: Canadian Family Physician • Le Médecin de famille canadien2009.

- Moureau NL, Alexandrou E. Device Selection. In: Springer International Publishing; 2019:23-41.

- Idemoto BK, Rowbottom JR, Reynolds JD, Hickman RL. The accucath intravenous catheter system with retractable coiled tip guidewire and conventional peripheral intravenous catheters: A prospective, randomized, controlled comparison. JAVA – Journal of the Association for Vascular Access. 2014;19:94-102.

- Chiricolo G, Balk A, Raio C, Wen W, Mihailos A, Ayala S. Higher success rates and satisfaction in difficult venous access patients with a guide wire-associated peripheral venous catheter. 2015.

- Campos CL. Enhancements in the identification of difficult venous access and the use of AccuCath. In: Yapici H, ed2020.

- Armenteros-Yeguas V, Garate-Echenique L, Tomas-Lopez MA, et al. Prevalence of difficult venous access and associated risk factors in highly complex hospitalised patients. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(23-24):4267-4275.

- Sebbane M, Claret PG, Lefebvre S, et al. Predicting peripheral venous access difficulty in the Emergency Department using body mass index and a clinical evaluation of venous accessibility. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2013;44:299-305.

- Lamperti M, Pittiruti M. II. Difficult peripheral veins: turn on the lights. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2013;110(6):888-891.

- He W, Goodkind D, Kowal P. An Aging World: 2015 International Population Reports2016, United Cencus Bureau.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, O’gden CLG, Naomi P. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017–20182020, CDC website.

- Prevention. CfDCa. National diabetes statistics report 2020: Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Published 2020. Accessed.

- Gregg EW, Li Y, Wang J, et al. Changes in Diabetes-Related Complications in the United States, 1990–2010. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(16):1514-1523.

- Hadaway L, Dalton L, Mercanti-Erieg L. Infusion Teams in Acute Care Hospitals: Call for a Business Approach An Infusion Nurses Society White Paper. Journal of Infusion Nursing. 2013;36(5):356-360.

- Medical L. IV Dislodgement Data. Lineus Medical. https://lineusmed.com/dislodgement. Published 2020. Accessed March 10th, 2020.

- MacArthur R. The Difference Between Central Lines and PICC Lines: What All Patients Should Know. https://www.myiv.com/difference-between-central-lines-picc-lines/. Published 2020. Accessed May 10th, 2020.

- Campos CL. Improving Patient Outcomes in Nurse-Placed Vascular Access Devices. https://sigma.nursingrepository.org/handle/10755/17236. Published 2019. Accessed January 27th, 2020.

- Hospital SVM. Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital – About Us. https://www.svmh.com/about-us/. Published 2020. Accessed March 10th, 2020.

- Infusion Nurse Society I. Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice. In:2016.

- Harpel J. Best practices for vascular resource teams. In. Journal of Infusion Nursing. Vol 362013:46-50.

- Moureau N, Chopra V. Indications for peripheral, midline and central catheters: summary of the MAGIC recommendations. British Journal of Nursing. 2016;25(8):S15-S24.