Dee Donatelli, RN, BSN, MBA, Sr. Vice President, Provider Services, Hayes, Inc.

There’s no question that great advances in medicine have been made over the last century. Still, not every medical technology, service, and intervention that we have at our fingertips is safe or works as well as, or better than, existing options. This is what clinical trials are for – to figure out how well a product or medical technology works and compares with other approaches, to identify when and for whom it should be used, and ultimately, to determine its clinical value.

If the clinical trial evidence shows a clear benefit, then we need to make sure we’re using the medical technology in the way in which it was intended—for the appropriate disease and patient population. This is what we call evidence-based medicine, a common buzz word that everyone seems to be talking about. But as we know, talk doesn’t necessarily align with behavior, does it?

Recognizing the need to incorporate evidence into our purchasing and utilization decisions is one thing. Being able to evaluate the quality of the evidence and understand how the data should impact our healthcare decision making is another. Once we commit to using clinically based criteria to make decisions about the items we use in the course of delivering medical services to our patients, the next step is to understand the evidence and to differentiate between good and not-so-good evidence. So what is evidence? Let’s define it simply as the outcome data derived from formal, scientific research. That’s it. Ideally, we want the evidence we use to be of the highest quality and to be unbiased; that is, we want the researchers to report the results clearly and accurately without any influence or bias from the clinical trial sponsor or any of the stakeholders involved in the research. Don’t consider the slick marketing brochures that sales representatives hand you or the testimonials that appear on manufacturers’ websites to be unbiased forms of evidence.

Unfortunately, not all evidence from scientific research is created equal. Assessing the quality and strength of the evidence isn’t easy. It’s not enough to simply review the abstracts of a few studies that the librarian at your institution pulled when you requested a search. A host of factors (study design, sample size, patient population, study execution, data reporting, etc.) impact the quality of evidence and these factors often aren’t apparent in the abstract alone.

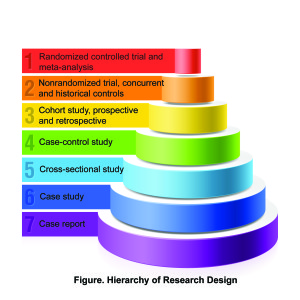

High-quality evidence begins with a suitable research design. The figure shows the basic hierarchy of clinical study designs. The weakest form of evidence comes from single case reports. These are the anecdotal reports of the outcomes seen in 1 or 2 patients. The strongest type of evidence comes from meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials (RCT) that enrolled enough subjects so that the results have meaning.

Keep in mind that we don’t always need an RCT to determine with reasonable confidence whether a health technology works and is safe. Sometimes, other types of studies provide high-quality evidence as long as they are well designed, well executed, and applicable to the patient population in which we’re interested. Moreover, even the best study can be fatally flawed if it’s poorly executed. That’s why it’s important to review the entire body of evidence, rather than just a few studies.

We need to look at all of the clinical evidence to establish an accurate perspective of a technology’s efficacy and safety. Cherry picking only those studies that support one position or opinion is a poor way to assess and compare the clinical value, and operational and financial impact, of new and existing health technologies. And since new studies are added to the body of evidence over time, any review of the evidence must be ongoing rather than a one-time process.

Good evidence has all too often been the missing link in our health technology acquisition and utilization decisions. It’s time for a new approach. Let’s remove marketing considerations, vendor-clinician relationships, physician preference, hope versus proof, and revenue potential from the process. Let’s focus instead on evidence that documents improvements in patient outcomes or operational efficiencies. By integrating high-quality evidence into our decisions, we have the potential to improve clinical outcomes, reduce waste and unnecessary costs, and make more cost-effective use of our limited healthcare resources. Isn’t that what we’re all trying to achieve?

Ms. Donatelli has more than 30 years of experience in the healthcare industry, with expertise in the areas of supply chain cost reduction and value analysis. Before joining Hayes, Ms. Donatelli was Vice President of Performance Services at VHA, Inc., where she provided executive leadership and direction for VHA’s consulting services, including Clinical Quality Value Analysis. She is a Certified Material Resource Professional (CMRP) and a Fellow of the Association for Healthcare Resource and Materials Management (AHRMM). She was recently elected president-elect of AHVAP, the Association of Healthcare Value Analysis Professionals. Dee can be reached at ddonatelli@hayesinc.com for questions or comments.

Hayes, Inc. (http://www.hayesinc.com), an internationally recognized leader in health technology research and consulting, is dedicated to promoting better health outcomes through the use of evidence. The unbiased information and comparative-effectiveness analyses it provides enable evidence-based decisions about acquiring, managing, and paying for health technologies.